Landscapes Stories _ Book Reviews

Dreaming Leone - Alvaro Deprit

Curated by Gianpaolo Arena

Self-published. First print run of 750 copies, 2014

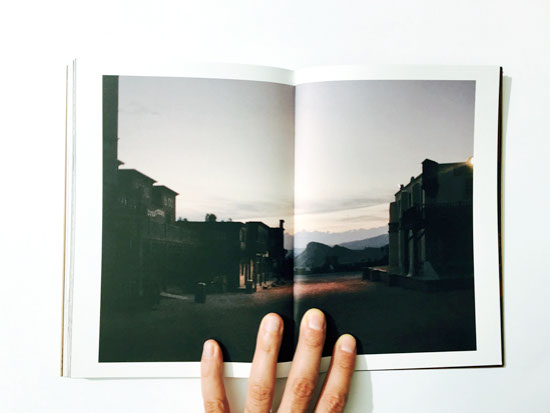

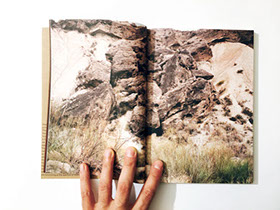

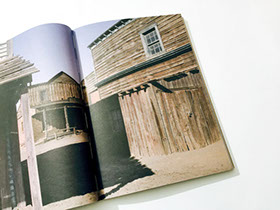

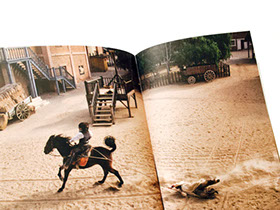

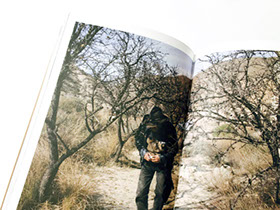

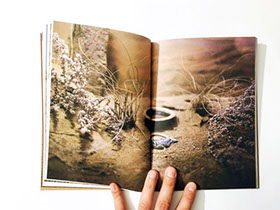

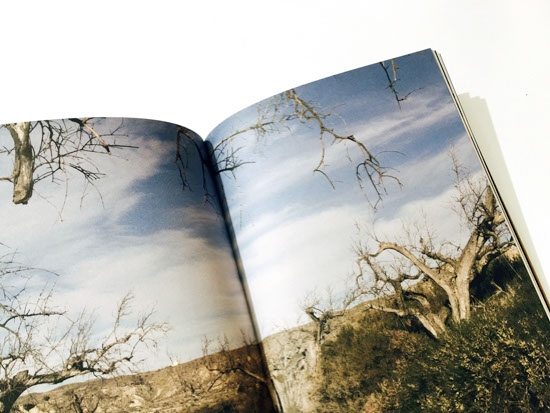

In the 70s and 80s, the Tabernas desert near Almeria in Southern Spain became the Hollywood of Westerns. It was here that legendary filmmaker Sergio Leone made movies like “Once Upon a Time in the West”, “For a Fistful of Dollars”, “For a Few Dollars More” and “The Good, the Bad and the Ugly”, making the desert of Tabernas, with its landscapes, movies sets, and relatively low cost, a point of reference for Westerns. In the 90s, filmmakers stopped making movies in Almeria mainly because the conditions were no longer affordable. The film sets were turned into fairgrounds or were abandoned, and the people who worked and lived around the cinema circuit, such as stuntmen and extras, dedicated themselves to doing Western performances to attract tourists. The economic crisis in Spain has also affected this industry, which is yearning for the glory days of Western movies. In reality, the performances for tourists evoke an era that is disappearing, and the faces of the performers reveals their melancholy expectation of an end that has already been announced.

The melancholy does not only come from the end of a golden era in the cinema: In this big scenario it has become an imitation of an imitation. Man tries to find a certain dose of fiction but not for a well-known necessity to evade but because he needs to find out about “the possible” apart from the real, what has been left out or could have been (and has not). In a historical landmark of the crisis and limited horizons the imaginary Western is the projection of a possibility west of the west.

Dreaming Leone Statement

-

“When I was young, I believed in three things: Marxism, the redemptive power of cinema, and dynamite. Now I just believe in dynamite.” (Sergio Leone)

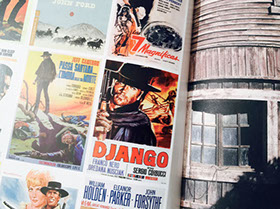

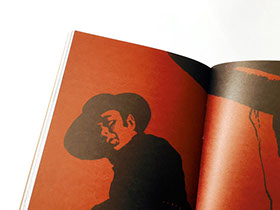

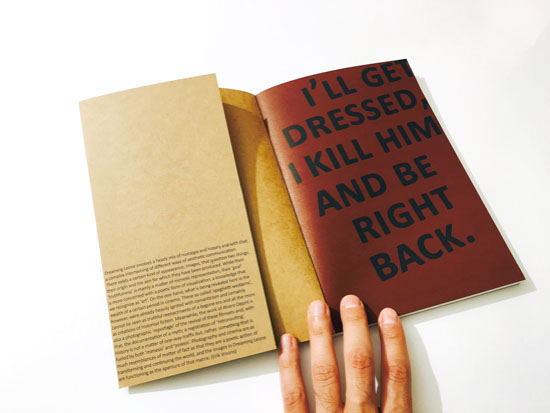

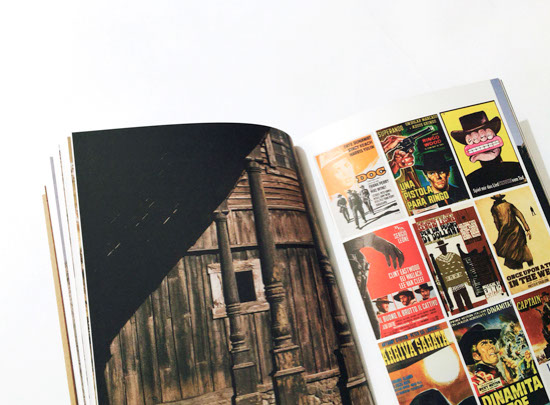

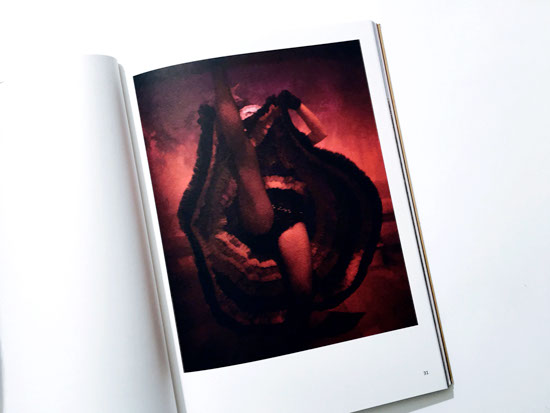

The “spaghetti western” was a broad subgenre of Western films that emerged in the mid-1960s in the wake of Sergio Leone’s film-making style. Most Spaghetti Westerns were made on low budgets, using inexpensive locales. Many of the stories take place in the Tabernas Desert in the Province of Almería in southeastern Spain. This area receives almost no rainfall, is very dry and looks full of wilderness. It was here that the filmmaker Sergio Leone made movies like Once Upon a Time in the West, For a Fistful of Dollars, For a Few Dollars More and The Good, the Bad and the Ugly. Violence, anti-heroes, a cruel world inhabited by fierce people, action, killing, gunshots is what you find on it. This cinematic landscape is an important part of the book that Alvaro Deprit created and edited in collaboration with Michela Palermo. The design of the book is really captivating and intrigant also with the help of the illustrations made by Francesco De Aguilar Milanese. The imaginary Western presented in the narration is the projection of a possibility of the west, an universe existent in our memory of the past. The melancholy of an era, the mistery and the ambiguity between reality and fiction, the possibilty to explore the landscape in a different way.

INTERVIEW with Michela Palermo

GA – Could you tell us something more about how your project ‘Dreaming Leone’ started? Did you start the project with the idea of making a book?

MP – Initially Dreaming Leone was a project for magazines by Alvaro Deprit. Since 2012 Alvaro has been working in a long-term project « AL Andalus » on Andalusia, a region in Spain where he grown up. During that time he was financed his research making editorial stories distributed by On Off Picture Agency. We have been both members of On Off Picture and we used to share works between us and feed back our projects, so I felt connect to the Dreaming Leone work since the beginning. Dreaming Leone has been published several times on different magazines and newspapers; mostly it was featured as investigation on the economical crisis of the film industry in Tabernas, Spain. At On Off Picture we cherished the goal of the publications and observed how the work was edited and featured in order to appeal to the editorial market. Alvaro was happy about the response of the photo editors – the work has been nicely published in Italy and abroad- but he was always a bit frustrated from the restriction imposed by the editorial frame itself (as editorial photographers we are both aware about the fact even if the best publication you can have will hardly pay back your former intention, and this fact is intrinsically due to character of editorials). In the summer of 2013 Alvaro asked me to explore with him the possibility of a dummy book about the work: I have been skilling myself in the book making process in the last years, attending workshop and being interested in the medium of photo books, producing zines and dummies for my own work. Looking at all his body of work, it was clear to me the potential of the story was not the inquest on the region and his economy, rather I’ve seen in the pictures of Alvaro a tribute to a vision rooted in the Spaghetti Western tradition, and of course to his inventor Sergio Leone. We started to follow this intuition, envisioning a narrative able to play correspondences with Sergio Leone’s legacy: spaghetti westerns movies informed our childhood memories and we were excited and willing to play with it. Alvaro was very keen to entrust his pictures to me, and to endorse me as editor of his work. As editor and designer of the book I had the chance to challenge his photography, grasping new meaning from the images, sequencing and lay outing them in order to build up an object could serve our idea of the book.

GA – How much were movies a source of inspiration?

MP – A lot. We are both fan of western movies tradition and it was a superb occasion to go over again to Sergio Leone filmography: it was a hot summer. We were corresponding about suggestions we caught from the movies: definitely the Sergio Leone’s movies – the mood, the colours, the environments, even the sounds constituted a sort of spine for developing the idea of the object we had, not just in the content of the book itself but also in the form we gave to it –for example in the choice of the materials we used.

GA – Please explain your role as designer and your working process…

MP – The photo book gives the photographer the opportunity to combine photographs and tease out a more complex meaning from them. I believe the role of the designer in a photo book is essential in the freedom of approaching to the work: I haven’t experienced what Alvaro did while he was shooting in Tabernas, that’s why I could use much more imagination in order to feel the atmosphere he lived, and I believe this approach triggers a new potential in the photographs.

For example in the sequencing I suggested to time lapse the scene of the cowboy who is fired. Alvaro told me about the fact this guy, working as stuntman, is fired 7 times at the days and this is how he gains his life -I was touched by this concept. In the editing, we had the power to bring him back to the life, inverting the sequence and let him to mark a sort of fil rouge in the book.

Another example was about the possibility to feel free to add to the narrative other visual elements without disrupting the photography of Alvaro. That s why the comics at the beginning and at end of the book, as in the movies you had these cartoons in the opening and credit titles, or the stickers, just in the middle, were a sort of inspiration from the interval you have in the movies’ screening.

I had to say we have been very lucky to involve in the project Francesco De Aguilar Milanese, an emerging illustrator from Spain, asking him to collaborate with us and to produce some sketches ad hoc we could use in the book.

We found strength in this form of collaboration: the kick from one of us was the goal for the other. So we started from the Alvaro’s work, going back to movies, moving forward to the photo book, and all the way around. And I believe this process has been extremely potential for the final result.

GA – Could you tell me about your attention for photo books?

MP – I’m a photographer and I do believe the photo book as an essential medium to enhance our work. During my photography studies, I was working as volunteer in the library of the school, shelving back a lot of books, most of time having the opportunity to go through them, before to put them in the right place. I started to collect them, I do like them as object (the smell, the tactile trait, the shape) and I do like the idea they are waiting me at home and each time I open them I feel the power to grasp new things according how my perception is changed (this happens especially when is a “good book”). Least but not last, I’m fascinated about the idea of the storytelling, and I feel photo books as bridges to connect things apparently far apart, and as extremely powerful tool for photographers to state their own vision.